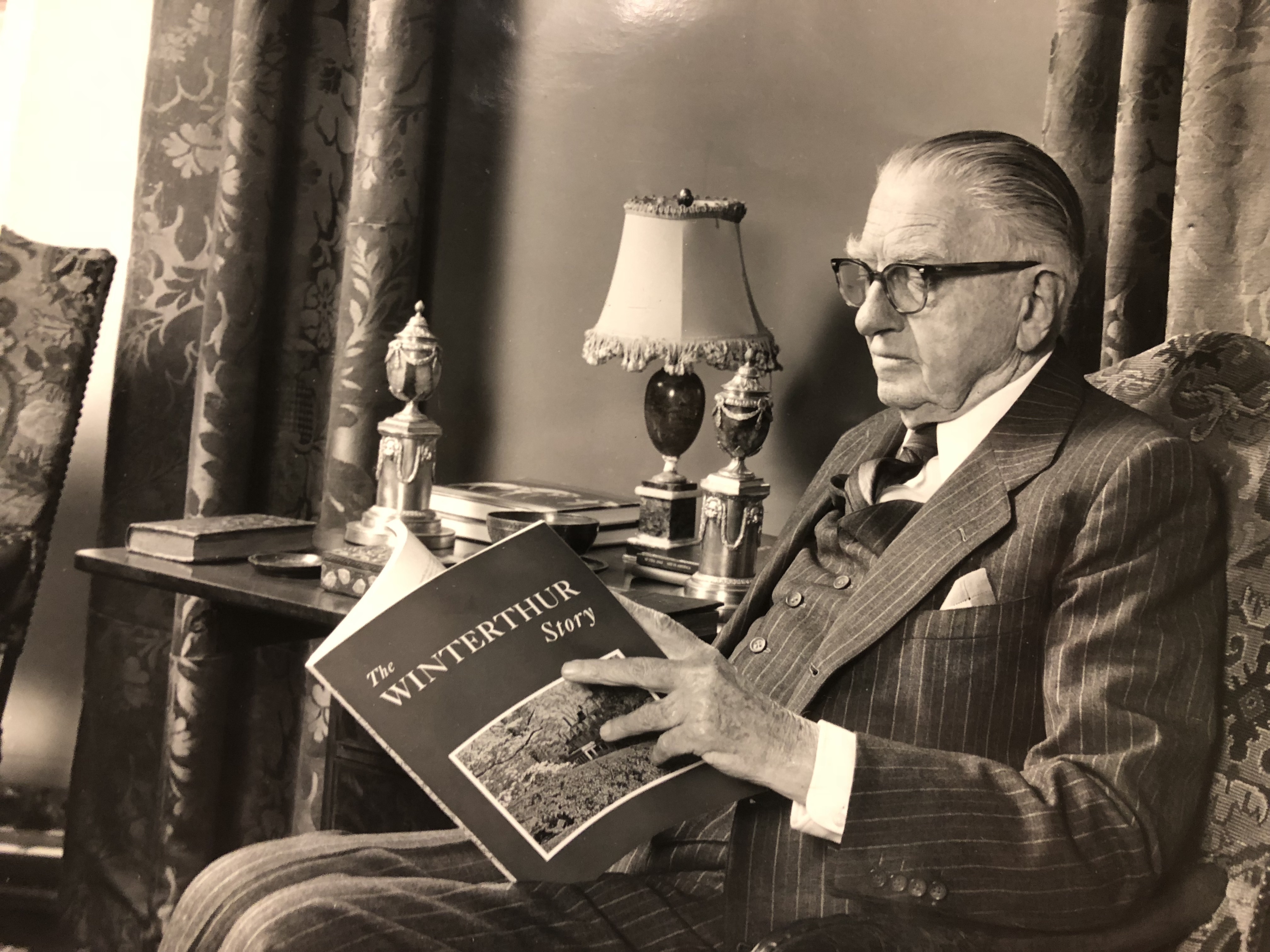

Henry Francis du Pont began collecting antiques in 1920s and amassed a collection of objects indicative of the “colonial” period or 1600 – 1880. With these objects, he founded his historic house museum that is now the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library. The collection consists of nearly 90,000 objects that are artfully arranged in domestic settings designed to evoke the spirit of the colonial period. He dedicated this museum to the study and preservation of early American material culture and founded a graduate program, the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, to foster and support the study of early American decorative arts.

So why would a collector so deeply rooted in early American decorative arts choose to furnish his museum in the midcentury modern style?

It is impossible to call Henry Francis du Pont a midcentury modernist writ large. But it is important to honor his legacy as a cultural influencer who borrowed from an array of design aesthetics. Du Pont was in no way a cloistered historian. He was a renaissance man who was friends with modernist icons such as Andrew Wyeth and Albert C. Barnes.

Henry Francis du Pont was on the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art, and in 1966, he attended the opening of the Whitney and wandered the galleries in Marcel Breuer’s modernist marvel. If he flew into New York he would have walked through Eero Saarinen’s TWA Flight Center which finished construction in 1962. Du Pont showed his support for modernism in his design choices and in the purchases he made. On April 4, 1956, the du Ponts bought a modernist Danish silver candlestick as a gift for close friend Miss Suzan Brand. Despite his interest in early Americana, modernism and midcentury material culture were a part of du Pont’s lived experience as a twentieth-century cultured man of the world.

He cared deeply about both his historic house museum and about building a professionalism around American decorative art.

The legacy of du Pont’s collecting should not be understood as separate from the work he did to advance the field of American decorative arts scholarship. The midcentury modern furniture at Winterthur was used in professional spaces, not the historic house museum. In this way, the furniture was installed to signal the important work that was being conducted at Winterthur. Though this was a place for the collecting and analysis of historic artifacts, it was a place that could foster innovative and progressive scholarship and thought.

Winterthur’s midcentury modern furniture collection should not be understood in opposition to its collection of early Americana. Rather, the collections at Winterthur presents the opportunity to find unity in form, function, and influence throughout American design.